COVID-19 Business Advisory Series

January 9, 2024

Transport Restrictions Pose Risk to Food Security and Income

January 9, 2024When President George Weah declared a national state of emergency on 8 April and banned travel between counties, he granted an exemption for activities relating to the production, marketing and distribution of food.

Yet, restrictions on movement are disrupting agricultural businesses, from input retailers to farmers and traders – similar to those logistical and transport barriers that challenged Liberia during Ebola.

Three individuals working across Liberia’s vegetable supply chain give their perspective on the challenges of growing and selling produce during the COVID-19 pandemic, from border closures slowing input supply to farming disruptions caused by curfews and difficulties in transporting produce to a market that is already depressed.

1. Border closures are slowing the supply of inputs to Liberia and raising product prices for farmers

Gertrude Gboko runs the Agricultural General Supply Store in Ganta, Nimba County. She sells agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertiliser to farmers and sources most of her stock from neighbouring Cote d’Ivoire. In recent weeks, border closures and travel restrictions in both countries have slowed the supply chain. Fortunately, it is still possible for Ivorian vendors to deposit some goods at the border.

“Goods can come small-small,” says Gboko.

Thompson Kpakilah, a trader, supplies inputs to farmers in three counties and takes their produce, from cabbage to watermelon and cucumber to tomatoes, to market in Monrovia once it has been harvested. “The cost of fertiliser is going up,” he says. “Goods are not easily crossing [the border], so we are using what is here now, and sellers have brought the price up.”

Another trader, Ezekiel Sayatee, who also works as both a sales agent for Gboko and a farmer in Nimba, describes how a bag of fertiliser which previously cost between US$30 and $35 can now retail at up to $50.

“There’s a worry the border closure will continue and agricultural inputs will be completely scarce on the market,” he says, adding that moving goods over the border is currently “almost like a black deal – you need to give extra money to grant permission.” These new costs, he believes, will be borne by the farmers who use the products on their farms.

2. Farming days are cut short by the daily curfew while a scarcity of vehicles means produce is kept waiting at farms post-harvest

Gboko reports that her sales have so far been unaffected by the COVID-19 restrictions as farmers continue to produce. But farming activities are facing disruption, as Gboko – also a farmer in her own right – understands all too well. While most Liberians are subject to a “stay-at-home” order, citizens who are permitted to continue their business activities must adhere to a 3pm curfew, which she says is affecting her ability to operate: “The time is very short even to go to my own farm!”

Sayatee notes how disruption to transport services is leading to delays in harvested produce leaving the farm. “Our produce is perishable,” he says. “We need to harvest on the day of travel. But now we have to wait one to two days before we can even get a car, by which point the goods have started to spoil.”

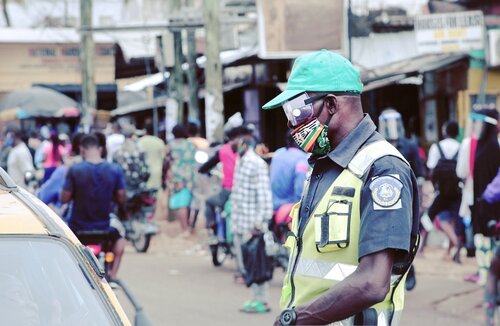

3. Getting produce to market costs more and takes longer due to social distancing directives and new checkpoints

The farmers’ difficulties are by no means over once a vehicle has been found to take their produce to market. Transportation costs – for both goods and people – have increased in the past month, in part due to a social distancing directive which limits the number of passengers permitted in a commercial taxi from six to three. Fares have in some cases doubled as a result.

Many commercial transporters have been deterred by the additional hassle associated with operating during the lockdown, leading to a shortage of vehicles plying the routes. A pass allowing transporters to operate during the lockdown, according to Sayatee, costs US$50, while vehicles are required to stop at multiple checkpoints erected to ensure they are complying with the new directives.

“We cannot travel freely,” says Kpakilah. “Going to from Monrovia to Nimba, we have to pass through more than 15 checkpoints,” he adds, noting that instances of bribery have increased.

The checkpoints, he continues, are leading to transportation delays: “In some cases, it has taken almost 48 hours from Ganta to Monrovia [the usual travel time is around four hours]. Produce will spoil on the way.”

Sayatee laments the increased cost of transporting bags of produce: “Usually it costs 300 Liberian dollars (LRD – or US$1.50) to transport a bag from Ganta to Monrovia in a commercial car,” he explains. “Now, it’s increased to 1,000 LRD. Can you imagine!”

4. Market? What market? Sales of produce have dropped, and prices with them

“Most of the farmers are complaining there is no market when they travel to Monrovia,” says Gboko, noting that corn sales are currently struggling. “People usually buy roasted corn from the street in the evening but not now because of the curfew.”

Gboko is concerned about the implications of this disruption on her business: “If the corn is waiting unsold in the warehouses in Monrovia, it will spoil and the farmers will not come back to me.”

Kpakilah has also noted a slowdown in sales at Monrovia’s Red Light market. “People are not buying,” he says. “They are minimising their spending because no business is going on.”

Cabbages used to sell for 4,000 LRD (US$20) per bag. Now, Kpakilah struggles to fetch 2,000 LRD. Combined with the depressed market and doubled transport fares, his commission along with his farmers’ profit have significantly reduced.

“Farmers are putting produce into cars and sending it to me,” he continues. “They say they’d rather see the vegetables spoil in Monrovia.

“Every farmer is a man sending his children to school and feeding himself. I can’t refuse. And if I don’t pay for the transportation, even though I haven’t requested the goods, next time the driver won’t take my load.”

“People are not coming to buy the way they used to,” agrees Sayetee. “I used to take 150 bags of produce to sell in Monrovia in one to two days. Now 25 bags won’t shift in a week. We are begging for people to buy from us.”

5. Disruptions are nothing new for vegetable producers and traders navigating an already fragile market system

The travel restrictions prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic are just the latest challenge to Liberia’s vegetable market system. Other recent obstacles have included:

- Intermittent gasoline shortages since January, which led to soaring transportation prices;

- The ongoing difficulty of securing a reliable supply of high-quality inputs at an affordable price, challenging production; and

- A depreciating Liberian dollar, which has reduced the affordability of imported goods necessary for production.

All of these challenges increase the cost of production and jeopardise a reliable domestic supply of produce for urban consumers, at a time when the government is seeking to increase Liberia’s self-sufficiency and food security. Facilitating the passage of inputs and produce – whilst respecting appropriate public health protocols – will be key to supporting production in the immediate term.

About GROW Liberia

GROW is an agri-business and investment advisory program that partners with businesses, investors, associations, and government agencies to accelerate inclusive economic returns within high growth industries in Liberia. GROW is supporting public and private partners and markets to respond to the COVID-19 emergency. Learn more about our research, advisory, and support here.

GROW Liberia © 2021 All rights reserved